|

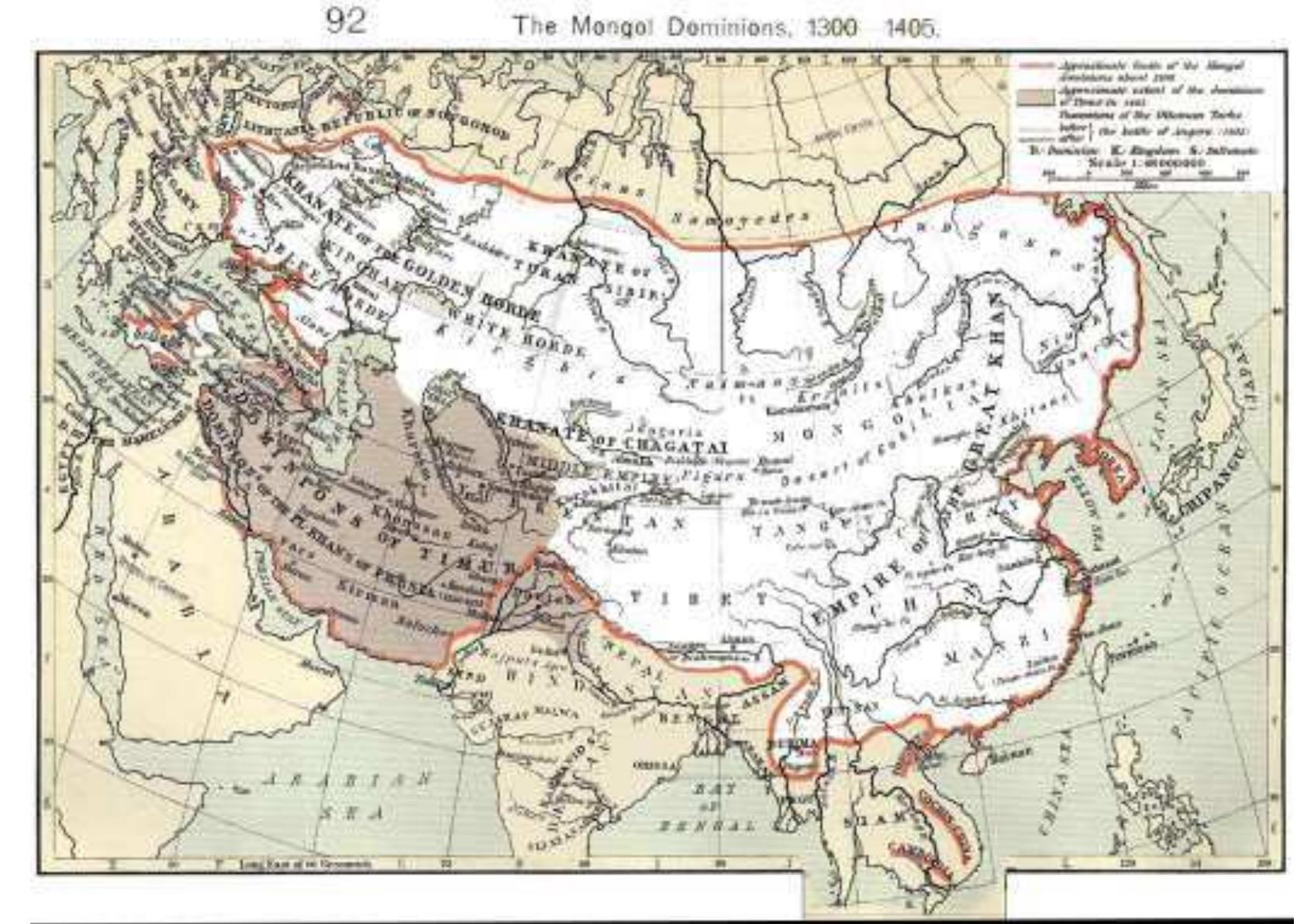

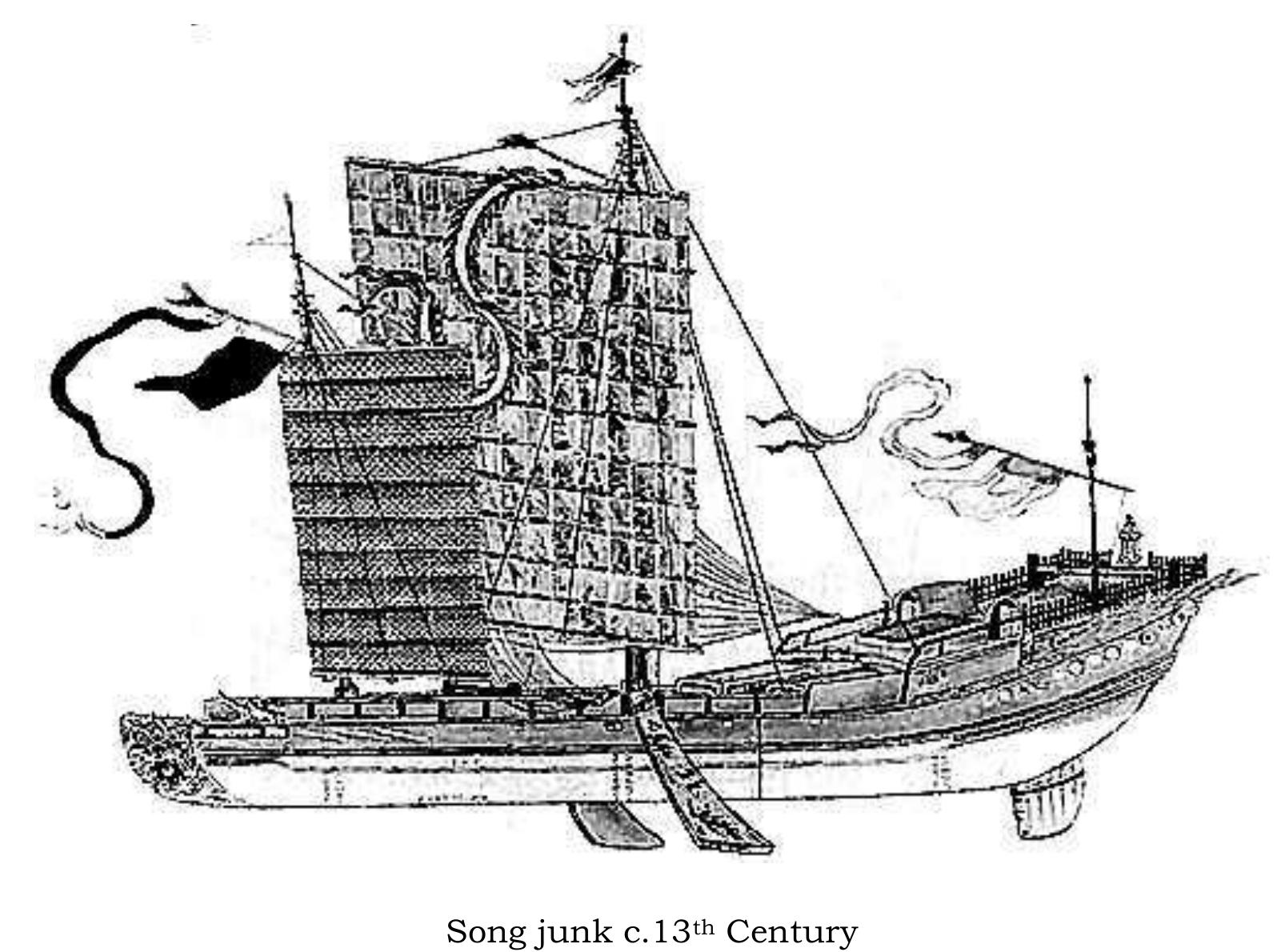

‘Lhe thirteenth century was a busy trading time for the South China Sea. Large ships ‘like houses’ travelled back and forth on the east-west maritime route, their ‘sails are like great clouds in the sky’.* Such were the descriptions of Zhao Rugua, the trade inspector of the main Southern Chinese port of Quanzhou‘ (Zayton or Zaytun was the Arabic name for this port, and one that Marco Polo refers to in his Book of Travels). Plying their trade between the Straits of Hormuz and Southern China, these merchant ships sailed close to the coastlines and used several stopovers along the route, in the Indian Ocean, the Malaysian peninsula, Champa and North Vietnam to take in supplies and more products before docking at Quanzhou. Spices, silk, ceramics, scented wood, forest products and rare animals were much valued at both ends of the maritime route, in the Islamic world and China under the Song.

After a period of consolidation following his appointment as Great Khan, in 1264, Kublai Khan decided to re-launch a campaign against the Southern Song. The previous campaign that he himself led had to be abandoned in 1259, after the sudden death of his brother and predecessor Mongke. The advance against the Southern Song was a campaign unlike any campaign that the Mongols had executed up to that point. The Song army, at the beginning, had much better weapons than the Mongols. Militarily, the Song had mastered the use of gunpowder and had created several kinds of bombs, either using incendiary devices or exploding metal balls containing metal fragments, to use against the Mongols.®

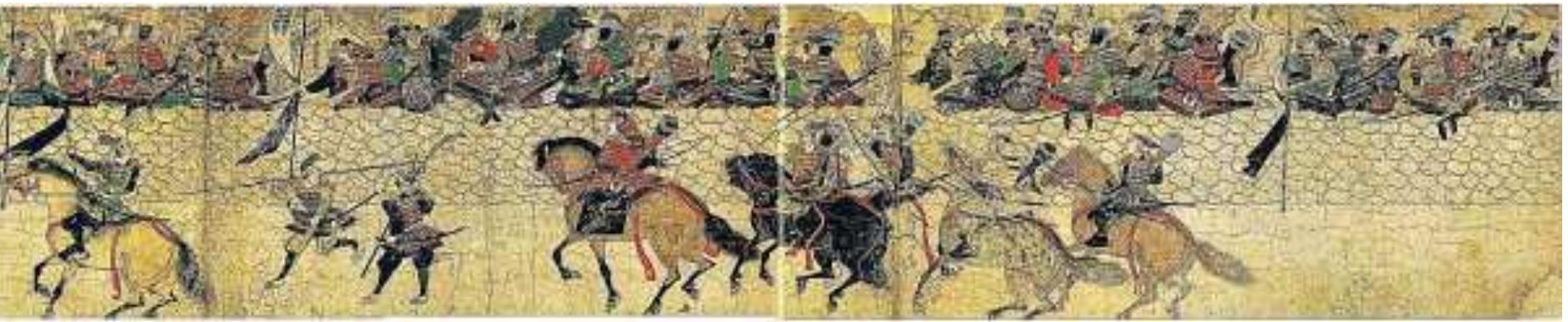

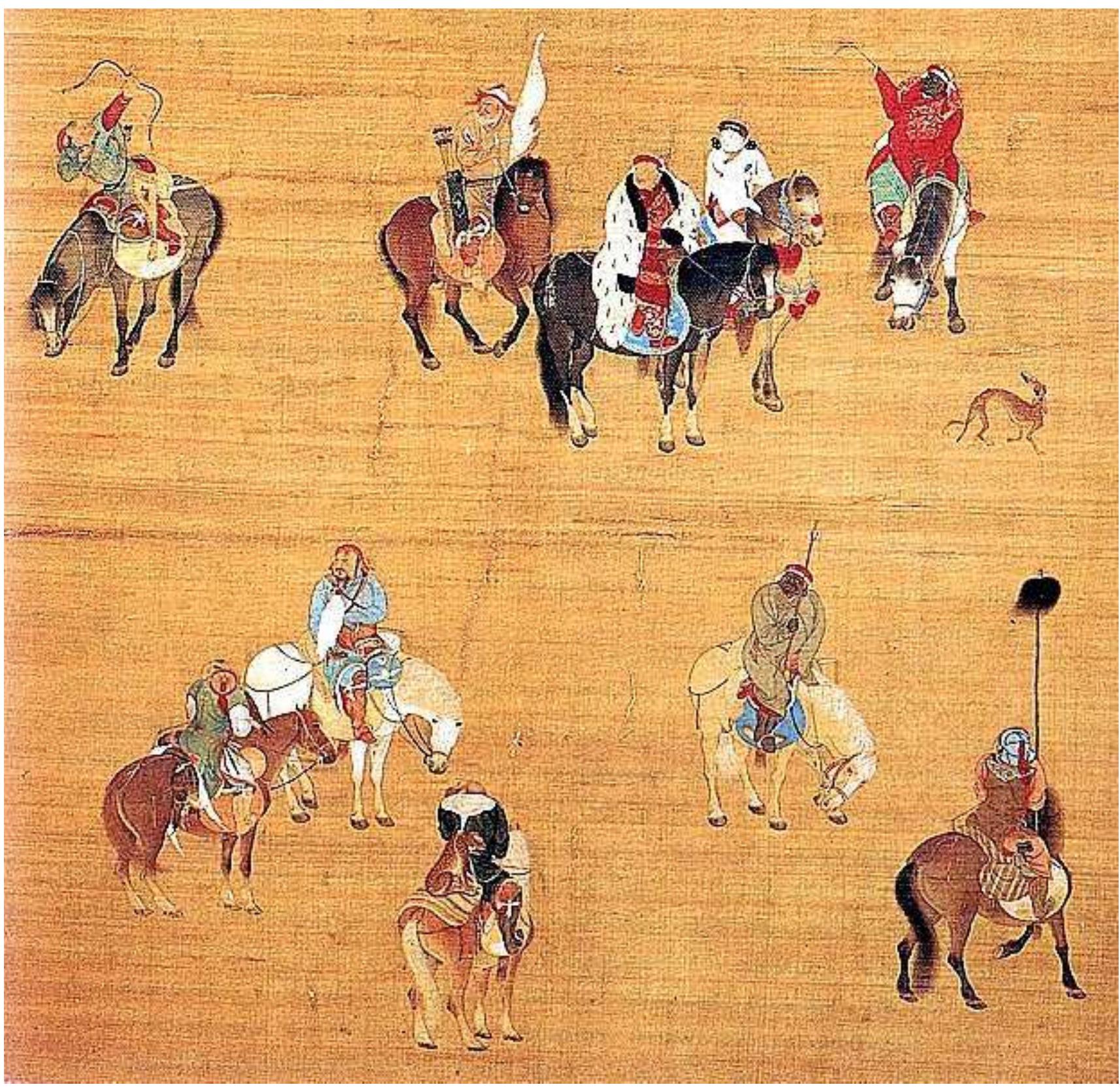

Mongol soldiers by Rashid Al-din Hamadani-14th Century Persian historian

in 1274.8 Whether it was all thanks to General Bayan or not, as this is still a debatable subject among historians, the battleground changed, for it was at that point that the Mongols began to use a waterborne force to complement their cavalry in southern China. The Mongol army now knew how to use the ships that they captured from the Song, or to make their captive sailors work these ships on their behalf, to cross or to travel up and down the huge rivers. In addition, the Mongols recruited more boats and ships from transport fleets already operating in southern Chinese waters. The Song Navy, in the thirteenth century, was one of the most advanced in Asia. When the Mongols started advancing into southern China, this Navy had already been organised into a ‘permanent fighting force and its strength grew steadily with time’, according to the historian Jung-Pang Lo.? By then, the Song Navy could travel swiftly ‘up and down different types of rivers and patrol the eastern sea to keep an eye on Japan and Korea’.!° They had also mastered some sailing techniques that land-locked people,

This failed invasion of Japan, interestingly, did not discourage the Mongols from sailing out to sea again, it may even have the opposite effect, for the Mongol ship-building programme was greatly intensified after that. In 1275, the Mongols began a production line at Jiangsu and Zhejiang shipyards to manufacture boats and ships, first for use on rivers.!° In 1276, Bayan enlisted the help of two former pirates, Zhu and Zhang, who came with 500 ships to join forces with the Mongols at the battle of Hangzhou. !© After the Southern Chinese capital fell, the former pirates undertook to transport the loots of charts, books and other treasures to Kublai Khan in Dadu, today’s Beijing, by sea. By using the sea route, they opened up a maritime transport tradition for the Mongols that they subsequently developed, using the Song Navy that they captured in 1279. In 1277, as soon as the Chinese eastern port of Quanzhou surrendered, four offices of maritime affairs were created in Quanzhou, Ming Chou, Shanghai and Kan-pu (in Taiwan).!7 ‘The next year, Mongol general Sodu (Sogatu or Sotu) and Pu Shougeng, a Muslim official in charge of maritime affairs in Quanzhou, were ordered to inform overseas countries of the establishment of the Yuan empire, and to encourage them to pay tribute and to trade.18 Between 1278 and 1290, Kublai Khan also sent seven

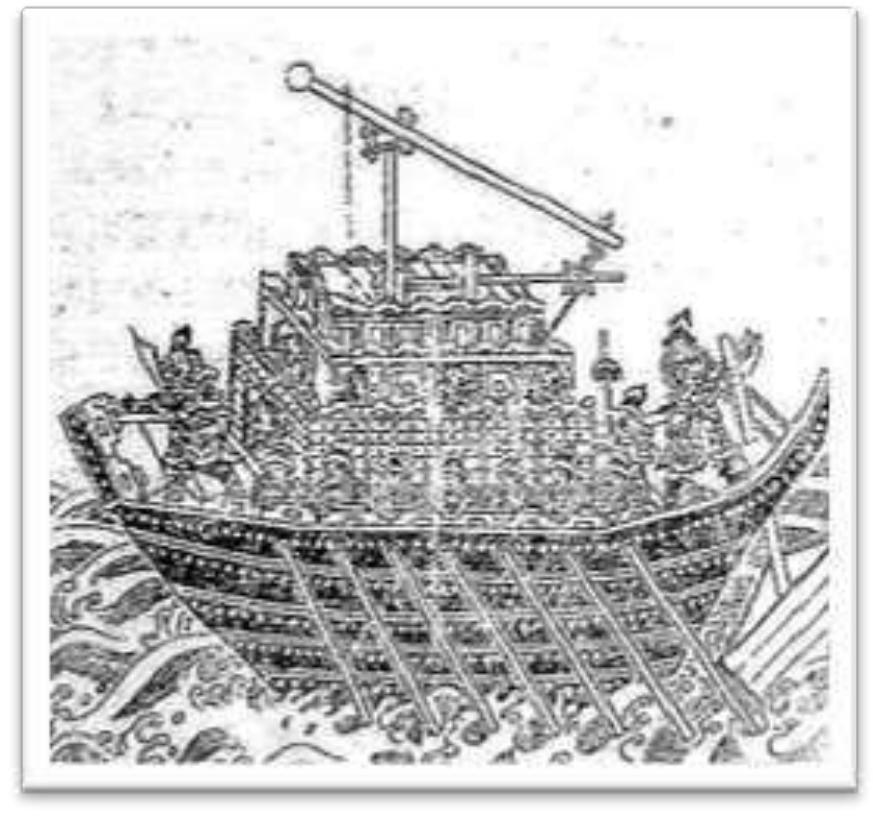

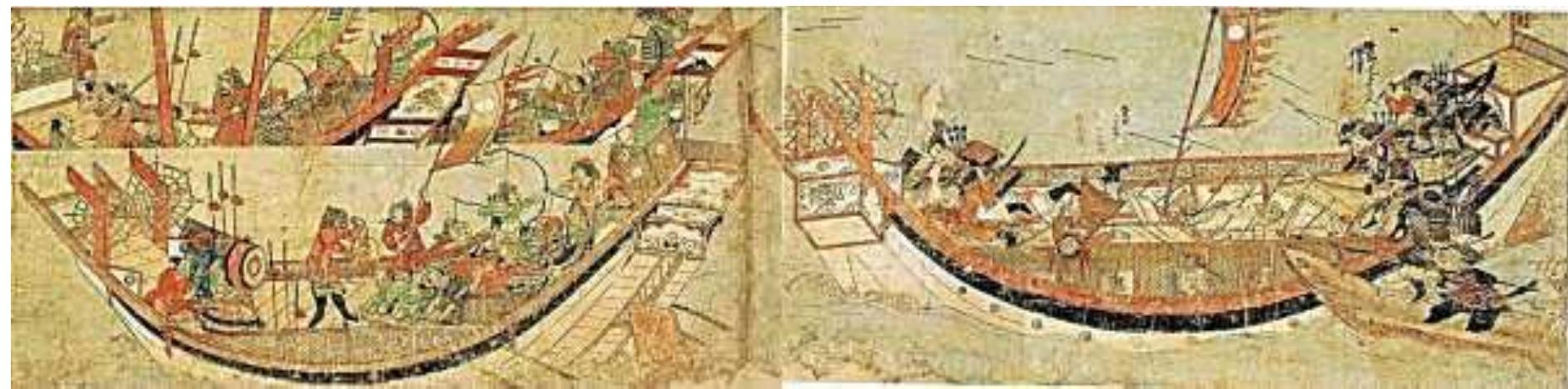

Model of Mongol ship — 13th Century In the same year, 1281, Kublai Khan ordered 3,000 ships to be built and 4,000 more ships in 1283.?° Shipyards were established in Chang-sha, Guangzhou, and even in Korea. The nearby islands of Quelpart and Taiwan and the Jehol uplands were ordered to supply wood for the ships. In one case, 17,000 men were mobilised to fell tree for timber and to transport them to shipyards in Jehol alone.2+ At the same time, the Mongols put the captured Song and former Korean officers in charge of directing all shipbuilding activities, and, to train a new generation of Yuan/Chinese sailors.

Mongol archer launched a ceramic bomb at the Japanese defenders Along with an intensified ship-building programme, the Mongols began to improve on the structure of the Song ships and built much larger models, based on the Indian designs that they had meticulously studied over the years, by sending scouts to the Indian Ocean on a number of occasions.25 The ships that Kublai Khan built often carried more than the 9 sails that most of their contemporaneous models used, some even carried twelve sails.2° Later Japanese archaeological research off the coast of Kyushu, from 1991 to 2003, proved that the ships that the Mongols built during those years had staterooms and watertight compartments for their cargoes and foodstuff, the food was stored in earthen jars.?” From the archaeological finds off Takashima, the size of the Mongol ships was estimated as twice the size of their European counterparts.2® The ships were also equipped with explosive devices in the shapes of ceramic bombs?? to be launched by longbows or catapults, a popular method of delivery at the time. It was not clear if the catapult-bombs were thrown from the ships, or just transported by ships and then set up for use on the beach, as during the second Mongol invasion in Japan in 1281.

In 1281, the Mongols felt confident enough in their naval strength to go, once more, to the islands of Japan. This time, Kublai Khan despatched a much larger armada of 3,500 ships and a mixture of forty-thousand Chinese, Korean and Mongol troops, along with one hundred thousand newly submitted southern Chinese troops.°° This second invasion of Japan was much needed for the Mongols to resolve some of the problems they had, after defeating the Southern Song, one of them was how to deal with the captured Song troops to avoid trouble in southern China itself. The idea was to settle them in Japan.

Japanese Samurai battled with the Mongols on the beach - 1281 This time, the campaign lasted nearly three months?! until, according to Japanese accounts, a strong Kamikaze wind began to blow, forcing the Mongols to leave the beach and retreat to their ships for shelter. The wind lasted for two days, during which, it struck the Mongol ships and destroyed a large part of their fleet. The survivors, again, hastily withdrew back to Korea.

Japanese Samurai boarded Mongol ships - 1281

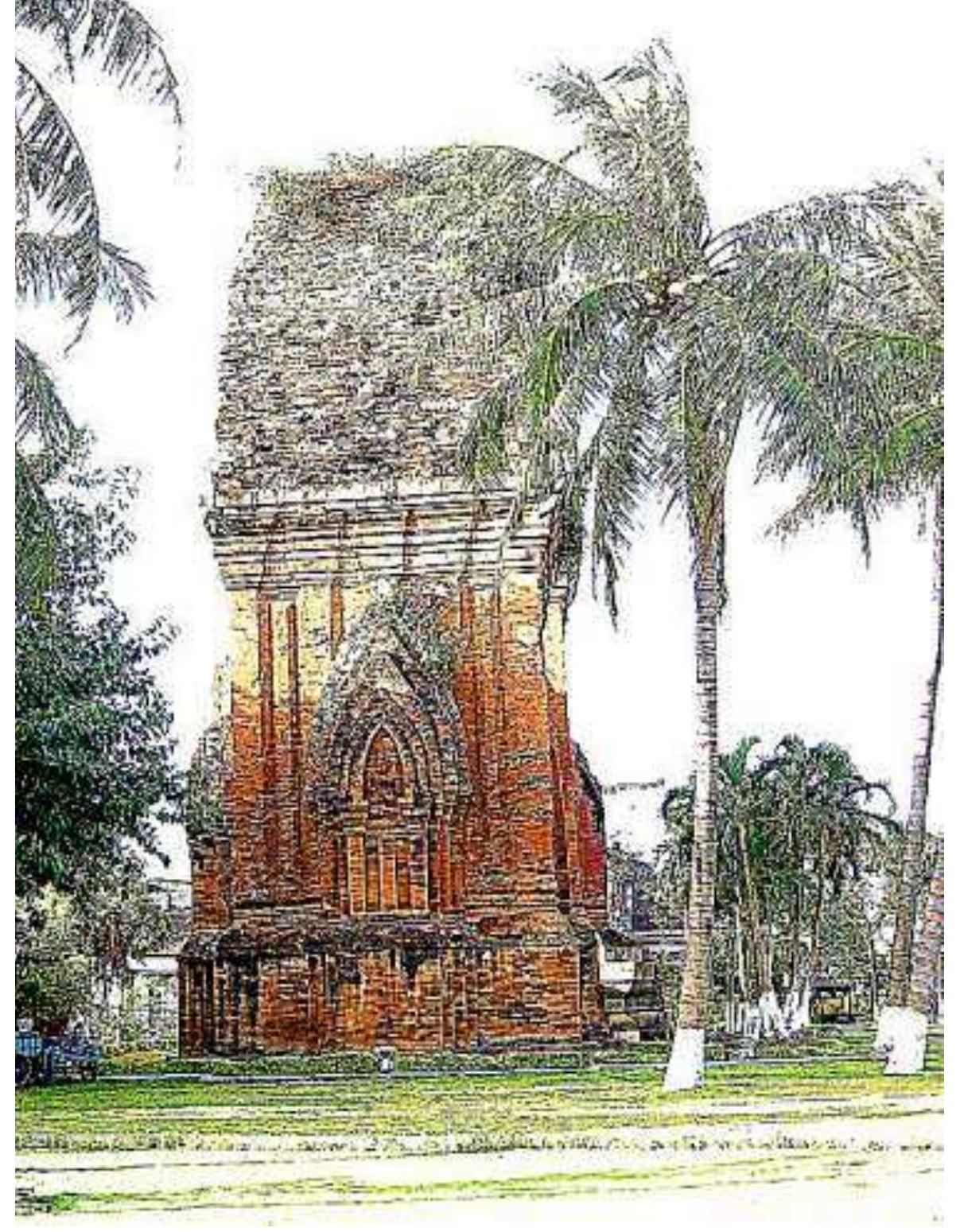

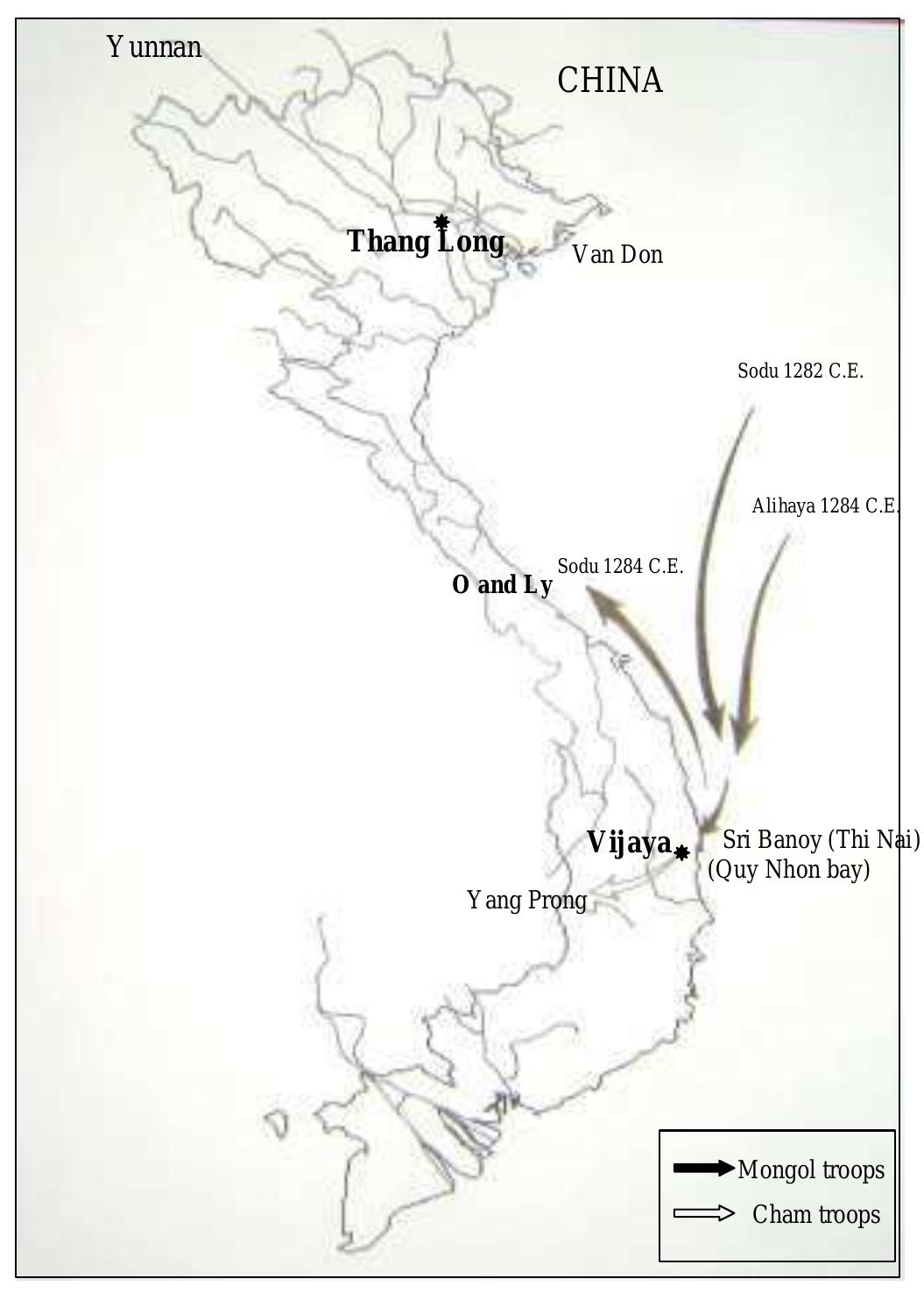

Prince Harijit. It was alleged that Marco Polo was involved in the process but, so far, this has not been proven conclusively by any official documents. From the Yuan perspective, Sri Banoy was an advantage that gave Champa ‘the power to disrupt or interrupt commercial or diplomatic relations between China and the countries of the south seas’,34 it would be beneficial for the Yuan to take control of it, not only to make use of its good geographical and commercial position, but also, to eliminate such threat of disruption. Wodu was given the title ‘Governor of Champa province’ in 1282, just before he set sail in the eleventh moon (December) of this year. The Mongol invasion fleet arrived at a port called ‘Estuary of Champa’ on the 30th of December 1282, a date noted by Pelliot as being omitted in Yuanshi but recorded in Jingshi dadian.*° His fleet was made up of 350 ships and a force of 10,000 troops, ‘including sailors’, under the

command of Sodu himself, a former Song naval officer Liu Cheng, and a Mongol general, Alihaya. On arrival, Sodu proceeded to make camp on the shore, and despatched several envoys to the Cham camp to ask the Cham king to submit voluntarily. His demands brought no result.%° Yuanshi recorded that he sent two envoys, travelling to the Cham camp seven times.37 The period of sending envoys back and forth was probably necessary for Sodu’s force and their horses to recuperate, after a long voyage at sea. The travel from Guangzhou to Sri Banoy was the longest seafaring attempt that the Mongol army and navy had yet undertaken in their maritime campaigns. Although Mongol envoys had been sent by ships to as far as India in the previous years, the Mongols’ earlier maritime invasions were to Japan, across a shorter stretch of open water, respectively in 1274 and 1281. The month long journey down the

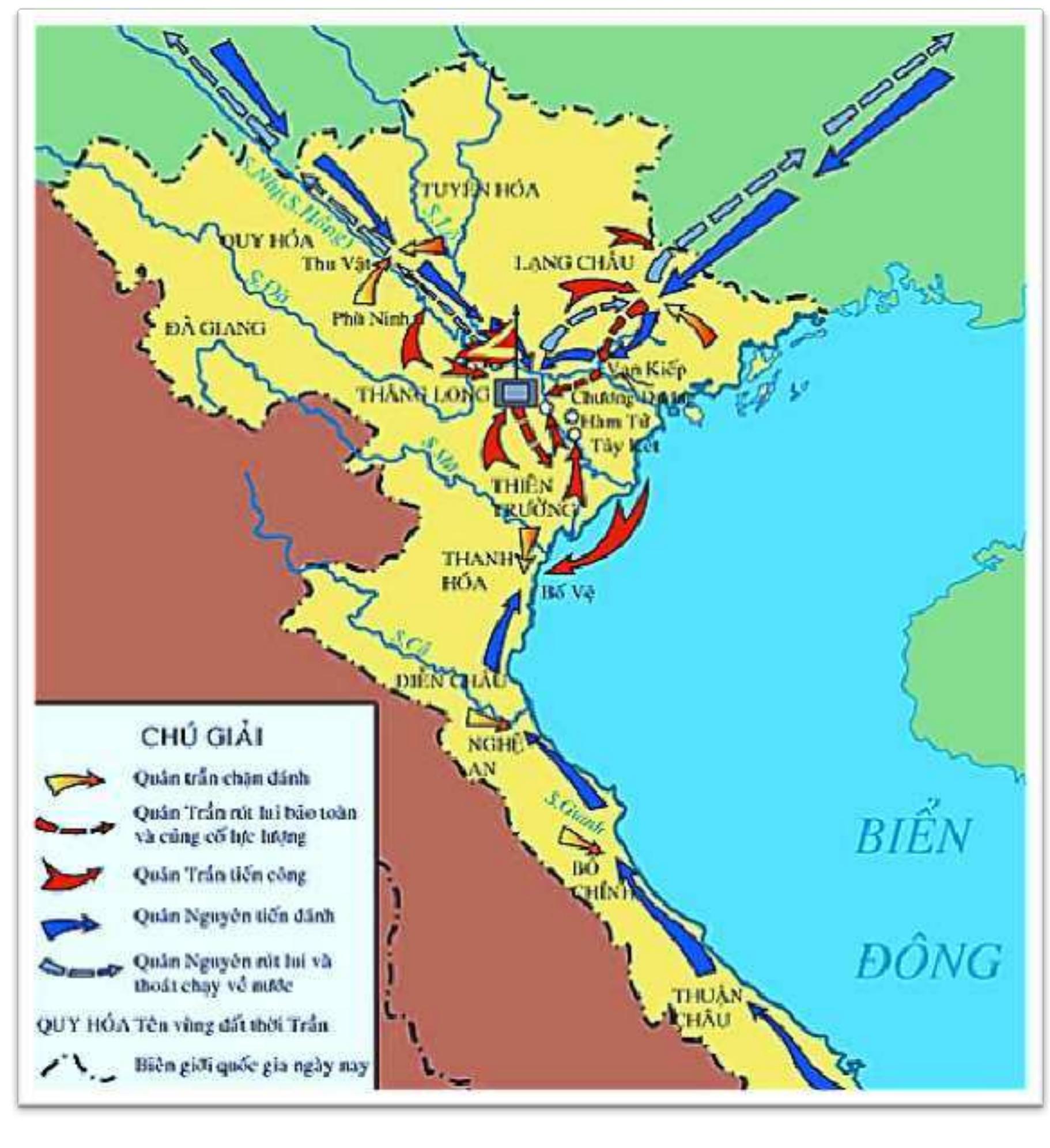

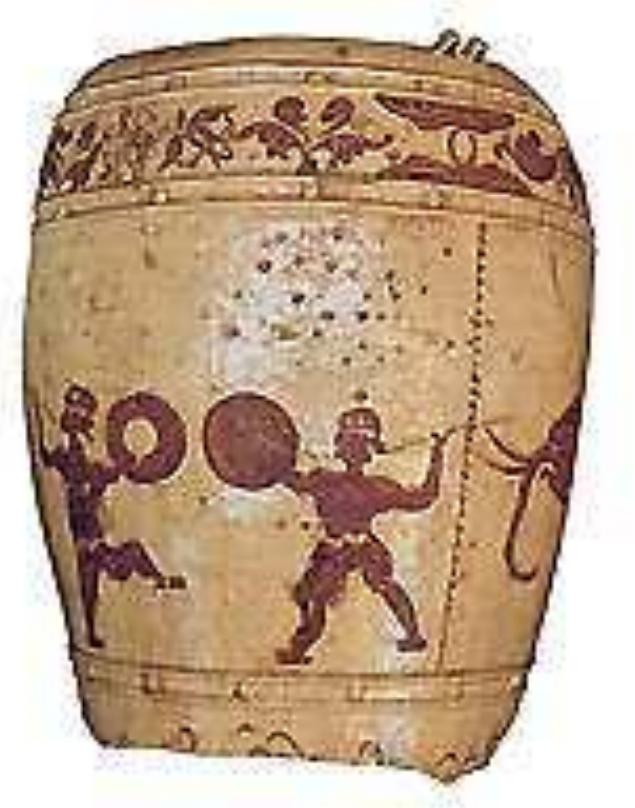

Tran soldiers - vase at The National Museum of Vietnamese History —- Hano ‘The Mongols crossed into Dai Viét by land and advanced south but they found that they had to cross many rivers along the way. Unlike in 1258 when the Tran had the advantage of their superior navigation skills over the Mongols, this time, the Mongol campaign in southern China had taught them similar skills. As they did not come with a waterborne force, Togan ordered general Omar Batur to establish a boat yard and build a number of boats, using local materials. When they had enough boats, Togan and Omar resumed their attack with a combined force of cavalry and river boats. The following battles between the Mongols and the Vietnamese were long and inconclusive. It was a situation similar to a hide and seeks, involving cavalry forces and foot soldiers on land and thousands of river boats of both sides.°© On the Vietnamese side, the emperor Tran Nhan Téng led a naval force himself, as commander of his imperial guards, said to amount to thousands of men.°7

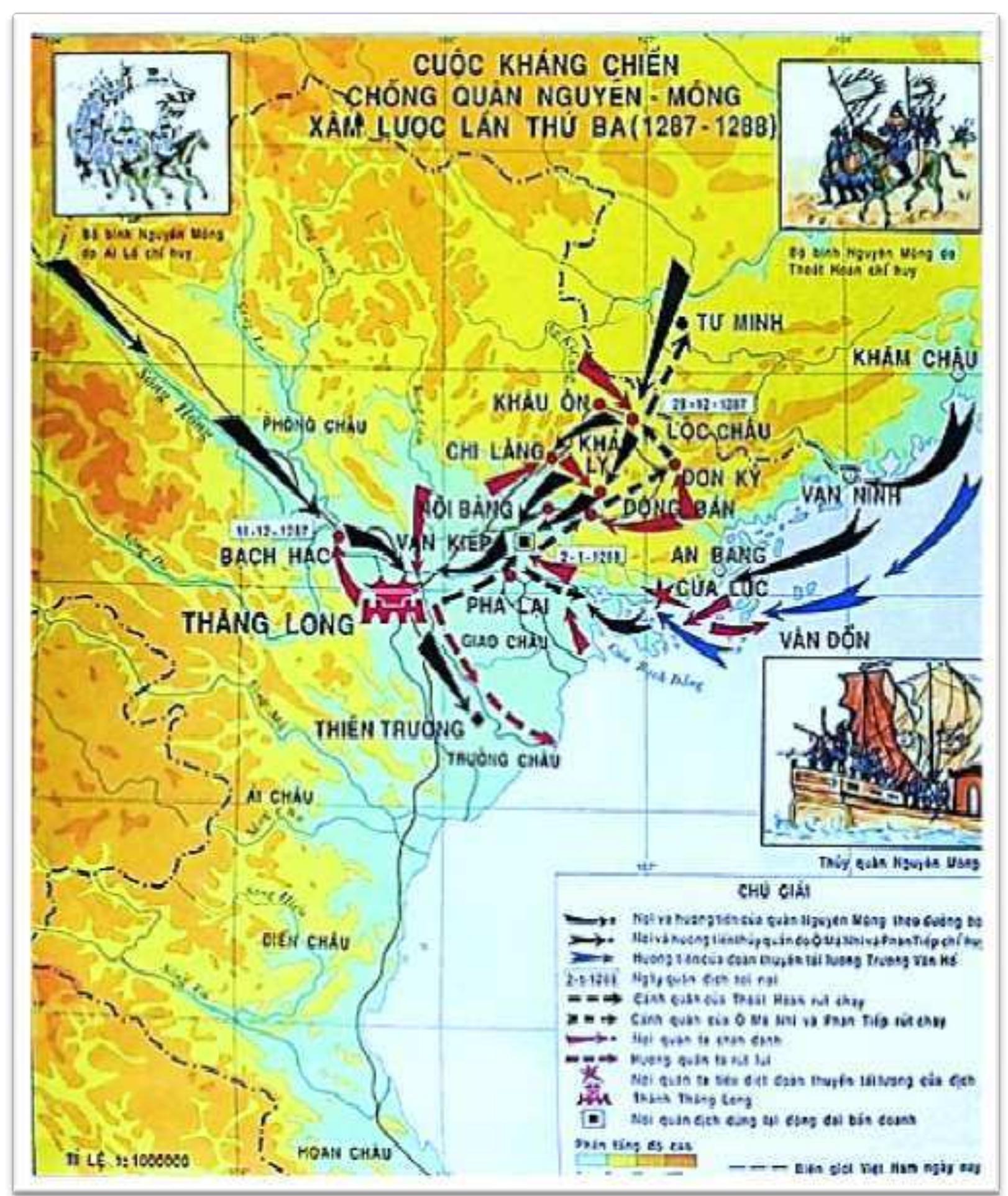

The third Mongol invasions of Dai Viét, 1287-8. National Museum of Vietnamese History - Hanoi fleet under General Omar Batur then met with the Vietnamese navy at Van Don.

Mongol horses in battle by Rashid Al-din Hamadani-14th Century Persian historian to Hainan island, leaving the Mongol land troops without supplies altogether. The loss of supplies was a massive blow for Togan’s and Omar’s forces in Dai Viét, for not only human foodstuffs were sunk, but hay and fodder for their horses were lost as well.°9 As noted in their previous invasions of Dai Viét, the use of horses was a problematic feature of Mongol campaigns in southern areas such as Dai Viét. Apart from the tricky terrain, the horses needed supplies, not just for the journeys, but also at local destinations. Mongol horses were bred and raised in the northern part of Central and East Asia, they would find it difficult to survive on local short grass, stringy leaves or rice straw, and even these were scarce in a small country like Dai Viét. For the Mongols, who relied heavily on their horses, and valued them as much as themselves, the lack of food and large-scale pastures for their horses in Dai Viét continued to be a disadvantage for them in this invasion, as much as it was during the two pnrevious ones in 1957-12958 and 1985. The beginning of the year of the Rat (1288) saw the victorious Mongols in Thang Long and the Tran emperors, once again, on the move, with both Togan and Omar in hot pursuit. Again, the Tran were saved by their expertise on river navigation. They managed to elude both Togan’s cavalry on the river banks, and Omar’s boats by using small boats to travel along the tributary system of the Red River. Togan then left the pursuit to Omar and went back to Thang Long.

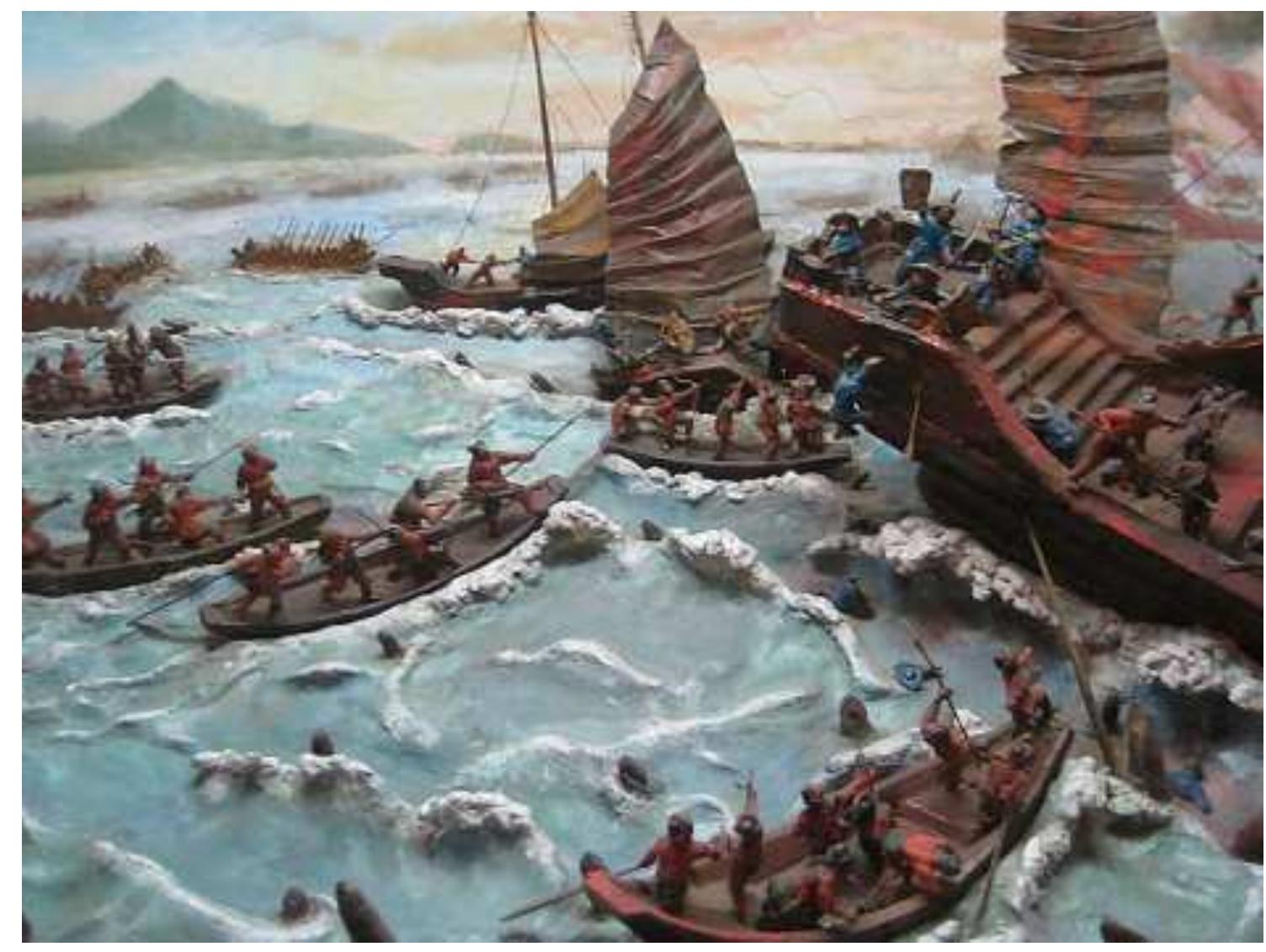

Dy then, although prince Togan was already occupying the capital, he still faced formidable foes in the shapes of the hot and humid weather, the lack of food and the spread of tropical diseases, most of all, he had had enough of the unreliable Mongol Navy. Togan decided to retreat back to China and ordered to burn all the ships.’2 However, he was talked out of the plan to burn the ships, allowing Omar Batur to take his fleet home by way of Ha Long bay. Togan himself took his army on foot back to China.

Model of the Bach Dang battle — National Museum of Vietnamese History — Hanoi

Bach Dang stakes — National Museum of Vietnamese History - Hanoi

(责任编辑:)

|